The earliest racing machines enjoy a huge presence, rarity and price tag to match, the alternative? A US Speedster that offered ‘muscle’ long before the phrase became popular.

It matters not your personal taste in motor vehicles, some machines just rock you down to your boots. This is true of the American La France Type 12 Speedster. If the sheer size (17ft long) doesn’t affect you, the details will certainly make you think. A straight six, 125bhp 14.5 litre engine with 18 spark plugs, 3 per cylinder with 2 coils feeding 12 plugs and the other 6 running to a magneto. The pistons are 5 1/2 inches in diameter thus you are doing well at 8mpg. The La France had no front breaks and the rears are contracting bands, offering a real challenge when bringing a 3.5 ton vehicle to a halt. The handbrake is often used when needed but prone to lock the wheels if over applied, something to consider at 90mph which is perfectly achievable once overdosed on ‘brave pills’; all this from 1914.

The European Story

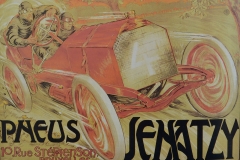

A fire truck offering a legacy that originates from the dawn of motoring, traceable back to the Daimler Motor Company and its Chief Designer Wilhelm Maybach. In 1899 a wealthy admirer of the marque named Emil Jellinek took the first 4 cylinder Daimler to Nice Week Speed Trials and entered under a pseudonym, his daughter’s name Mercedes. Just a year later the Mercedes name was adopted for Daimler cars available in parts of Europe and the US. Again in 1901 after much persuasion by Jellinek a 5.9 litre producing 35hp was readied for Nice Week. The Mercedes 35hp tourer would become the forefather of the modern motorcar, no longer resembling a horseless carriage. In 1902 Maybach would design the Simplex which at the time was light years ahead of the competition and a chassis costing £2200 offered 70mph performance. The Simplex models were uprated for racing and glory followed including winning the Gordon Bennett Cup in 1903 with an engine producing 90hp and setting a new world record in 1905 at Daytona. Little wonder the design was widely copied. The Crane-Simplex Automobile Company in the US began to build similar versions using Mercedes parts.

American La France purchased two rolling chassis and converted them into fire trucks after which they copied the design from Crane-Simplex and built their own versions; consequentially many of these fire trucks have since been ‘de-serviced’ and converted to the Speedsters offering close replica’s with extraordinary performance. The La France Company did produce an estimated 22 passenger cars including just 2 Speedster versions; few are known to exist today. Edwardian designs of this type are rarely seen therefore these copies offer a chance to view some of motoring’s pioneering high performance race cars on today’s roads.

The Stateside Story

In 1903 the American La France Fire Engine Company came into existence, although enthusiasts of the marque have traced its roots back to horse drawn carriages seventy years prior. The names behind the company were John Rogers who began producing manual fire pumps in 1832 and Truckson La France who had been producing similar equipment since 1873. Combined, American La France would be the main producers of fire-fighting equipment for over a century and their first motorised vehicle arrived in 1907. Unfortunately the company has all but ceased to exist, once operating from Elmira, New York. They produced thousands of vehicles over the years but in the early days adapted a range of appliances to fulfil their requirements; this included taking the biggest, most powerful cars and modifying them for the task. The machines they did produce were special order only and were often referred to as ‘chief’s cars’ whilst others were known as ‘pumpers’, as were the examples here. La France is reported to have been interested in producing not just Speedster versions but also racing versions to take on the ‘dirt tracks’. One Type 8 La France was built but then abandoned after Truckson witnessed a racing accident that resulted in fatal consequences. It would be unlikely many, if not any of the La France Speedsters would have ever raced in period as up until the mid-1920’s they were expensive to purchase and by the time they became affordable their competitive time had passed, although that hasn’t deterred many from adapting them over later decades.

Edwardian Hot-Rod’s?

Built to look like pre WW1 race cars the vital component is getting the vehicles proportions correct thus creating the correct period image. Many of the early race cars like Simplex, Mercer, Mercedes and Fiat used large displacement engines and chain drive. Since the early American LaFrance fire trucks were built using large displacement T-head engines and chain drive, they are the perfect candidates for early speedsters. Debate rages as to whether the Speedster and the early Gow Jobs/Hot Rods are one and the same, I looked to one explanation from someone with authority on the subject. ‘’A Gow Job is a low-line vehicle usually a roadster made up of the parts of several different vehicles and home-built speed parts. A “Speedster” was a roadster with cut-down bodywork, resembling a “real” race car, but retaining some of the more comfort/safety oriented features of standard street cars, like fenders (often smaller than standard, but still there), windscreen(s) and often a small trunk. These were the first sports cars and were either factory/coach built, or a production car with an aftermarket body retrofitted after initial purchase of the vehicle. Some had minimal bodywork behind the seats with exposed gas tanks, while many ended up with torpedo or boat-tailed bodies’’. Model T’s and Model A’s are popular adaptions Stateside and with most early Speedsters from pre WW1 their oversized power plants remained, often having ample cubic capacity when originally installed although tales of folk fitting aero engines are common place, many from wartime fighter aircraft.

The earlier La France trucks had a $5k purchase price ensuring most of these machines would remain in standard form for many years and built with such a robust quality many continued their fire-fighting duties for decades. These earlier chain drive models from the marque based on the Simplex design were still being produced over twenty years after La France supplied their first customer. Thereafter many would remain in fire truck spec for years with enthusiasts preserving their originality whilst others would be converted, often when they were well passed pensionable age. The longest endurance events, such as the Peking to Paris, nearly always feature a La France and it takes a certain passion to own and maintain such a vintage of machine whilst understanding the ingenious engineering that is now a century old; one such man is Julian Grebby. Reasonable knowledge is required just to get a 100 year old engine of this size to fire; time for me to listen and learn. Fuel on followed by primary and secondary ignition. Decompress the exhaust valves followed by an offer of £50 if I fire her up on the starting handle, I declined. When facing a cold start thimble sized cups sit on top of the cylinders, one shot of fuel into each and a turn of the brass handle drops the extra measure into the bores. A starter motor the size of a small bucket spins the huge iron flywheel and produces a strange grating noise common with these engines, then with a roar that is guaranteed to make you jump, six pistons each big enough to accommodate a grown man’s hand are forced into action. My first sighting of the Type 12 from 1914 was appropriately at the Laon Classic Festival in Northern France. The La France was many spectators ‘star of the show’ whilst blasting around the closed roads of the old town. The offer to view the town and acknowledge the crowds from the passenger seat of this ‘green goddess’ was a chance for me, not to be missed and never forgotten.

Another Chance with the La France

Meeting up with Julian again at his home in Kent offered the chance to understand the La France, quiz the custodian and admire another Speedster from the marque; yes he has two. Both Type 12 versions but yet quite different, for this reporter Christmas had arrived early. Julian began his interest in La France with an original fire truck complete with ladder and additional lighting. Imported from Tom Laferriere in the States this 1918 vintage was ‘too nice to convert’ Julian divulged, so his only option was to look for a converted example. A trip to Brooklands Auction provided the solution with his first Speedster. Later he was given the opportunity to purchase the 1914 machine which offered all he wanted in a La France; the fire engine was sold. They share the same power unit although both have enjoyed some sympathetic alterations including alternator conversions using the flywheel as belt drive. The green car I enjoyed in France is dated 1914, has a more pronounced Speedster look and with its slightly shorter chassis sits much lower than the later 1918 machine from Julian’s stable, height reduced by the 24in rims. The later alloy bonnet version runs 26in wheels and is fitted with a Zenith Carburettor whilst the green machine is fuelled by a Schebler version; an Indianapolis company that later became Borg-Warner. Mechanically both cars share the components with the same T head motors and three speed gearboxes driving the impressive chains to the rear wheels. In true Speedster fashion the earlier version has also benefited from the weight shedding losing nearly a ton in the process. Visually there are noticeable differences, especially the height of the later car with the peak of the bonnet reaching 5ft above the ground. It runs open wheels whilst the earlier car has period mud guards and a pair of individual leather seats and the area over the dash from the bulkhead has been reduced. The earlier green car is certainly much more the ‘Speedster’ whilst the later version is even more imposing, winning the ‘mines bigger than yours’ contest with its huge alloy bonnet.

Board the Beast

On the road the La France requires a skilled hand to master and control; luckily the owner is more than capable and we not only make progress rapidly but have a turn of speed that surprises me considering it’s of a vintage that warrants a telegram from the queen. Julian is able to muscle the Speedster through narrow country lanes with confidence and at one point my modern turbo diesel needed ‘foot to the floor’ to keep pace. It is however from the passenger seat where it really impresses, with constant input from the driver into the huge steering wheel, timing adjustments, right hand gear change and my biggest fear a central throttle pedal. One incorrect stab on that control and several tons of rolling thunder could easily cause mass destruction but my pilot was in total command; it was like watching someone handle the world’s biggest Rottweiler on a very short leash. Take off is all or nothing and the Hickory Wood wheels spin easily, especially in the wet and the three speed crash box is worked hard but once into top the La France hitched up her ‘breeches’ and just pulled relentlessly. The vibrations are immense and the sense of speed heightened, being high up with no screen for protection makes a blast in this Speedster more exhilarating than anything Disney has to offer. Edwardian race drivers would be expected to handle such machines at insane speeds, for many hours, over rough terrain; little surprise there was so many accidents. A thrill and a privilege to be aboard such a vehicle; my thanks must go to Julian for offering the opportunity to bring these magnificent machines to a wider audience.

Ahead of Their Time

One description I have read sums up the Speedster ethos; ‘they are creations where people take what they think are the best aspects of the Mercedes, Simplex, Stutz and Mercer etc and build a car to suit themselves’. Machines at the very forefront of motorsport competition in their day, offering technology that made great strides in a short time. It was motorsport that brought these lightened yet seriously powerful giants to the public’s notice. In America only a few purpose built race tracks were available before 1914; Indianapolis first saw action in 1910 and several dirt tracks had been converted from horse racing to satisfy a growing need for motorsports. The first board tracks would soon be opened and they became extremely popular attracting huge crowds into wooden velodromes, although their safety record would see many close. Motorsport in the US had been slower off the mark than in Europe; the Vanderbilt Cup did offer an alternative to the dangerous capitol-to-capitol events across the Atlantic, America’s first International Road Race in 1904 featured 18 such machines. Sponsored by William K Vanderbilt the course over 30 miles was on closed roads around Long Island NY and 10 laps would be required by the competitors, cheered on by 50,000 dangerously close spectators. The winning car averaged 52.2 mph but just 4 years later the event had attracted 250,000 and the average speed had increased to 64.3 mph over 258 miles but each lap now included nine miles of concrete, the rest though was still uncovered dusty roads, it wouldn’t be until 1908 that an American driver won the Vanderbilt Cup. The desire was there and the machines were available, whilst in Europe by 1907 races consisted of circuits around towns; less dangerous maybe but many road surfaces were still rutted and dusty tracks. One example was Dieppe in France where the lap was a mere 48 miles (small in comparison to most) and the overall distance was 10 laps; the winning car was able to average over 70mph for the race. Cars became more powerful and the drivers more daring whilst the circuits slowly improved the speeds increased substantially; so did the fatalities.

Story and Photos contributed by: Grant Ford, UK